I have been asked information about «The Upper Room», a play published posthumously. I have to confess that I haven’t read because I have not been able to find it. All I can say is what Martindale wrote in volumen II of Benson’s biography.

I have been asked information about «The Upper Room», a play published posthumously. I have to confess that I haven’t read because I have not been able to find it. All I can say is what Martindale wrote in volumen II of Benson’s biography.

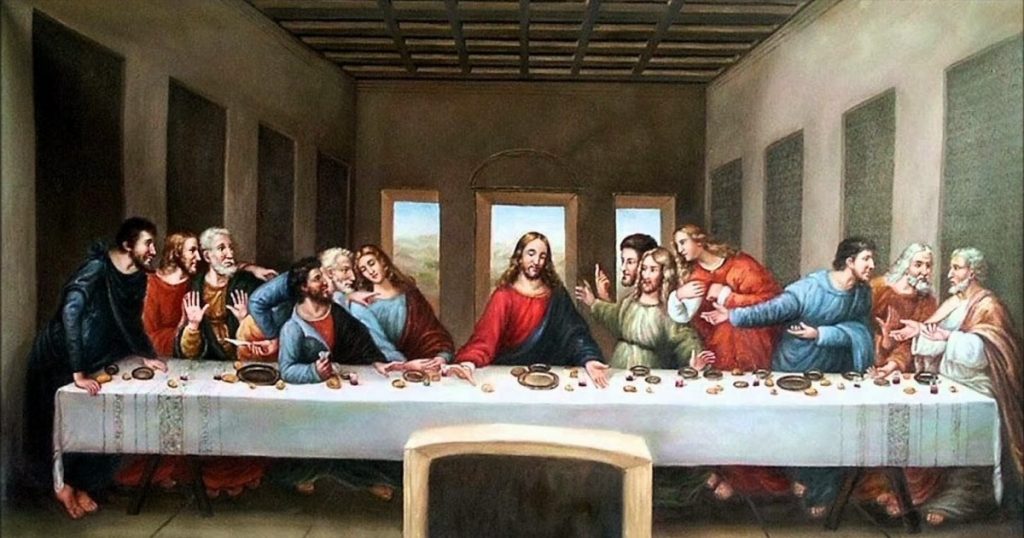

«The Upper Room appeared posthumously in November 1914; its introduction is reminiscent, by Cardinal Bourne; and its preface had to indicate, as was best possible, the author’s intentions for his play. It was to be partly symbolical, the preface urges : not realistic. Hence the Supper-table will suggest (though not imitate) an altar, with its cloth and candles ; Peter will carry keys, and Mary will put the Grail into the Arimathean’s hands. Benson will emphasize the symbolic value even of persons when he can; he boldly accepts the translation, » and HE was Night,» for the et erat Nox of the Vulgate, when Judas leaves the supper-room.» (» And Night he was who ran.»)

The action passes altogether in the Upper Room, over the parapet of whose balcony torches, spear-heads, or the three crosses are observed to pass (as the third cross passes it is seen to reel and disappear, for its bearer fails). Beyond, at the back, an idealised hill of Calvary is seen, black against the starlight, or dawn, or the streaked sky of Good Friday, for the action extends from the departure to Gethsemane to the return from the entombment. It is divided into three scenes, of which the second is a kind of tableau ; above the stripped table, where the candles are extinguished. Calvary is seen with vividly black crosses, very far away, and the Reproaches are sung. All the liturgical Passion music is introduced in some part or other of the play.

Naturally the whole piece is charged with a high emotion, and its literary aspect does not, and is not intended to, force itself upon one. The ungracious instinct of criticism suggests to a reader at any rate that very unequal reminiscences of a mediaeval style, and some disconcerting echoes of Tennysonian rhythm and even diction (as, for instance, of the Idylls of the King), somewhat mar the sternly ecclesiastical manner which should, I fancy, be that of this play. That Mary should here be called » a very Queen of men for gallantry» seems wholly out of place, and in the earlier part of the first scene there are too many phrases of a sort of facile lusciousness : » The air turned faint with incense,» a line written in connection with the Last Supper, jars terribly in a story for which the reticence of the Gospel record has for ever set an irreformable example. But it is for acting, not reading, that this play was swiftly written ; and it seems the graver pity that on one occasion at least its performance was, at the last moment, vetoed by authority, on account of the presence on the stage of Mary, who speaks, after all, only a few lines of epilogue. As the years went by, however, the desire to write a play which should be a London success grew till it amounted very nearly to a passion. He made acquaintances wherever he could with authors or actors, in order to learn stage technique; he would sit, in an armchair placed for him in the wings, and watch rehearsals ; he would go, whenever this became for him legitimate, to see the plays themselves—in Scotland, for instance, and constantly in America. He displayed, however, great annoyance when a rumour was spread to the effect that Father Benson had declared that priests ought to go to theatres whenever they legitimately could. («Curiously, I cannot find one example of his going, after he became a priest, to hear an opera, despite his keen love of music.”·)He was delighted, on the other hand, with Mr. George Mozart’s opinion that priests would find no better or more willing Catholics than among members of the theatrical profession, if only they would display the «sporting spirit» of Father Benson, and go round and meet them at the stage door.»

C.C. Martindale, Life of monsignor Robert Hugh Benson, vol. II (Longmans, Green & Co., London 1916), pg. 326-328.

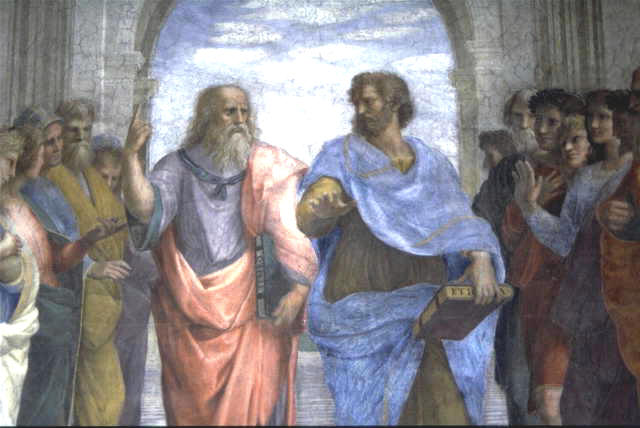

Cápsulas filosóficas: grandes ideas en pequeño formato

Cápsulas filosóficas: grandes ideas en pequeño formato